Alexei Navalny’s memoir, particularly, reminds readers how essential the freedoms to vote and dissent are.

That is an version of the Books Briefing, our editors’ weekly information to one of the best in books. Join it right here.

If I had been to assign one guide to each American voter this week, it might be Alexei Navalny’s Patriot. Half memoir, half jail diary, it testifies to the brutal therapy of the Russian dissident, who died in a Siberian jail final February. Nonetheless, as my colleague Gal Beckerman famous final week in The Atlantic, the writing is surprisingly humorous. Navalny laid down his life for his ideas, however his sardonic good humor makes his heroism really feel extra attainable—and extra actual. His account additionally helps make clear the stakes of our upcoming election, that includes a Republican candidate who has promised to take revenge on “the enemy from inside.”

First, listed below are 4 new tales from The Atlantic’s Books part:

Now, if I had sufficient time to assign voters a full syllabus, Ben Jacobs’s new listing of books to learn earlier than Election Day could be the proper place to begin. Literature on campaigns of the previous presents a “well-adjusted different” to doomscrolling or poll-refreshing, Jacobs writes, recommending 5 works that put the insanity into much-needed perspective—together with H. L. Mencken’s account of a raucous Democratic conference; Hunter S. Thompson on worry, loathing, and Richard Nixon; and a deep dive into the chaotic 2020 presidential transition.

Navalny’s memoir takes place below a really completely different political system, but it surely, too, covers presidential campaigns, together with his personal try to problem Russian President Vladimir Putin (Navalny was in the end barred from working), in addition to loads of different chaotic management transitions (from Mikhail Gorbachev to Boris Yeltsin to Putin). These will not be the convulsions of a mature democracy—in the present day, Putin guidelines as a dictator—however in Navalny’s unrelenting good nature, there are glimpses of what a Russian democratic chief may appear like. (He may be a Rick and Morty fan; he may construct a purposeful authorized system.) Embedded on this martyr’s story—what Beckerman calls “the fervour of Navalny”—is the tragedy of a world energy that missed the possibility to construct the type of open society Individuals now take with no consideration at their peril.

Essentially the most elementary freedom of an open society often is the proper to vote, even when, as in america, the selection is constrained by a two-party system and the foundations of the Electoral Faculty. In an ideal world, maybe a protest vote wouldn’t be a wasted one, as Beckerman famous in one other story this week; a poll wouldn’t rely extra in Pennsylvania than in New York; a presidential selection wouldn’t should be binary. However Patriot jogged my memory that Navalny additionally voted—realizing it was futile. He tried to run for workplace, realizing he’d be punished for it. And he saved talking out from jail, realizing he would probably die for it. He did these items out of optimism. He thought his nation would sooner or later be free: “Russia will probably be completely happy!” he declared on the finish of a speech throughout one in every of his many present trials. If he may consider that, then Individuals, whose rights are safer however not essentially assured, might be optimistic sufficient to vote.

A Dissident Is Constructed Completely different

By Gal Beckerman

How did Alexei Navalny stand as much as a totalitarian regime?

What to Learn

The Pink Elements, by Maggie Nelson

In 2005, Nelson revealed the poetry assortment Jane: A Homicide, which focuses on the then-unsolved homicide of her aunt Jane Mixer 36 years earlier than, and the ache of a case in limbo. This nonfiction companion, revealed two years later, offers with the fallout of the sudden discovery and arrest of a suspect due to a brand new DNA match. Nelson’s exemplary prose type mixes pathos with absurdity (“The place I imagined I’d discover the ‘face of evil,’” she writes of Mixer’s killer, “I’m discovering the face of Elmer Fudd”), and conveys how this break upends every part she believed about Mixer, the case, and the authorized system. Nelson probes still-open questions as an alternative of arriving at something remotely like “closure,” and the way in which she continues to ask them makes The Pink Elements stand out. — Sarah Weinman

From our listing: Eight nonfiction books that can frighten you

Out Subsequent Week

📚 Carson the Magnificent, by Invoice Zehme

📚 Lincoln vs. Davis: The Warfare of the Presidents, by Nigel Hamilton

📚 Letters, by Oliver Sacks

Your Weekend Learn

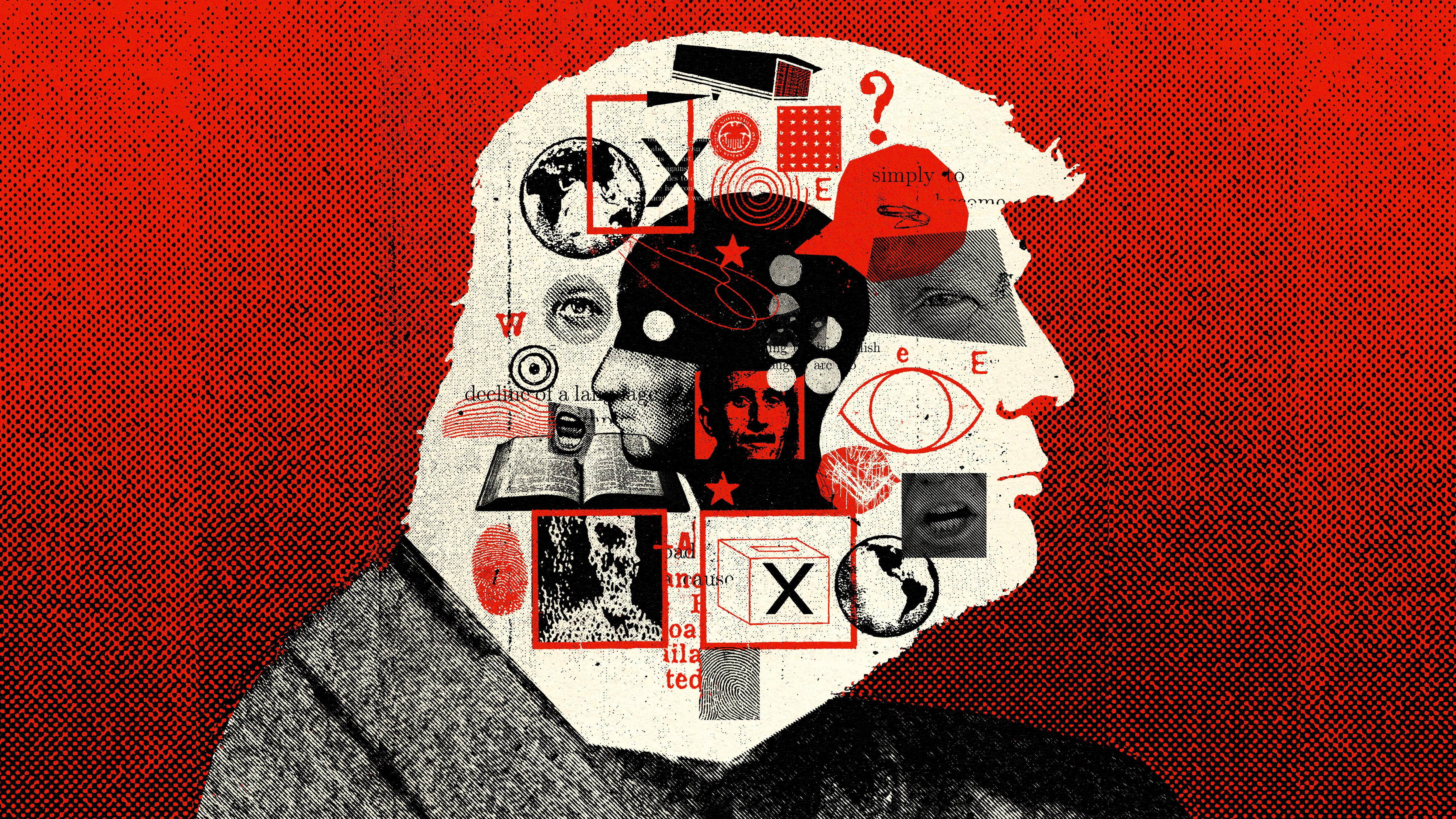

What Orwell Didn’t Anticipate

By Megan Garber

“Use clear language” can’t be our information when readability itself might be so elusive. Our phrases haven’t been honed into oblivion—quite the opposite, new ones spring to life with giddy regularity—however they fail, all too usually, in the identical methods Newspeak does: They restrict political potentialities, somewhat than develop them. They cede to cynicism. They saturate us in uncertainty. The phrases may imply what they are saying. They may not. They may describe shared truths; they may manipulate them. Language, the connective tissue of the physique politic—that house the place the collective “we” issues a lot—is shedding its potential to satisfy its most elementary responsibility: to speak. To correlate. To attach us to the world, and to at least one one other.

Whenever you purchase a guide utilizing a hyperlink on this e-newsletter, we obtain a fee. Thanks for supporting The Atlantic.

Join The Marvel Reader, a Saturday e-newsletter by which our editors advocate tales to spark your curiosity and fill you with delight.

Discover all of our newsletters.